22 July 2010

Adolph Gottlieb: “Another thing – I have changed my mind about an idea of Milton Avery's – as he says, 'don't try to paint a masterpiece.' It seems to me now that that is the very thing to do – try to paint a masterpiece – it probably won't be one anyway. Of course, from his point of view, Milton's right, there are many pictures that would be pretty good if they were not belabored and worked to death in trying for perfection. But right now I am sick of the idea of all the pretty good pictures and want a picture that is either damn good or no good.”

“Pretty good” can be oppressive.

Gottlieb stayed with what I consider a landscape grid in later years, which kept it in the spirit of Max Ernst's canvases (below) which were his main influence. Ernst created Pollock, Motherwell, and Gorky, and then the next generation turned dogmatically against representation, which is turning against infinity. That's my main beef with abstract expressionism, which I otherwise like. When something becomes standardized, the first thing to go is infinity. I haven't undertook to write about the avant-garde on this blog so far except to stress this point.

Unexpected charms in the Ellsberg documentary just out on dvd, like the nugget that when his defense lawyers consulted a psychologist about whistle-blower jury selection, the advice was to avoid middle-aged people. News you can use.

19 July 2010

The most pleasant storm this summer, though it didn't last long, beginning with cooling spiral winds that moved the leaves against a white sky, the smell of a distant fire and a nearby TV that had some African music which seemed at first not the be a TV, then the thunder moving closer and the rains, and with the clearing, first blue sky with puffy clouds to the west and then the north as well. Cage says your Mozart CD sounds the same every time. I am overcoming two fears, that of the thunder when it gets close, and also that a tree, less than a foot from the storm observation structure, about three feet from my own feet, is climbed by a family of raccoons, a mother and four children, and though I have been known to feed 'em in the past I found it at first disquieting to have the raccoons physically above me, where a slip could hurl it through the screen and on to my lap. In both cases I've made peace with the law of averages. On the other side where my laptop is, the raccoons are now walking down another tree. Cage liked the noise the cars make on 6th Ave., Sebald: “For some time now I have been convinced this it is out of this din that the life is being born which will come after us and will spell our gradual destruction, just as we have been gradually destroying what was there long before us.”

13 July 2010

I'm glad I saw this without knowing who the speaker was, so that I could wonder about the back story. At first I wondered whether the person was in the Himalayas (which I have been reading about) but Yosemite was on the video title. I thought that the person was camping, not accustomed to people having this sort of view in front of their house.

Comments about this video on Huffington Post and Youtube illustrate how one conditioned response to the perception of nature relates to another conditioned response. Vasquez is happy not just about the double rainbow, but the fact that the double rainbow validates his rationalizations to live at the precise spot where he lives and, by extension, his persona, which is organized around immersion in nature and Indian heritage. A person on a camping trip would be more likely to think such a rainbow was routine, or perhaps be socially conditioned to relate their enchantment in a more understated manner.

Vasquez denies being on drugs, though he admits to drug use at other times. I'm not saying I don't believe him, but he would have incentive to say that he isn't on drugs, as admission to drug use may inhibit the media promotion of the video. Reactions to the ecstatic reaction to the double rainbow often center more around people's opinion of the morality of drug use than how nature should be appropriately rendered linguistically. Of course, people's perception of these two issues overlap, though many dedicated campers are anti-drug, people who have low opinions of drug users often have low opinions of naturalists.

Without question, Vasquez views this as a religious experience, and the ecstasy traditionally associated with religious experience has always elicited divided reactions. What interests me more, though, is how understatement functions: the fact that the creed of linguistic understatement is in this social division aligned with apathy towards nature while overstatement is here aligned with affirmation of nature. Other situations, such as the excitement over the economic benefits of a strip-mining project, would align overstatement and understatement differently. My fear of being at an analytical distance to the baroque cannot be separated from the fear of fate, or fate operating as the fear itself.

12 July 2010

09 July 2010

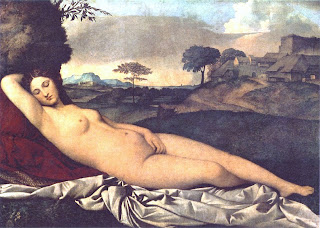

I've received confirmation from Dresden that Augustus II purchased Sleeping Venus in 1699, though the provenance is sketchy before that. It seems reasonable to assume the painting stayed in the Casa Marcello before then, during Velasquez' visits, since it had been a prized possession. Sleeping Venus was the first of many paintings acquired by Augustus, a Venice enthusiast who perhaps wanted in on his namesake's claims to divine right, as Caesar Augustus' stepdad (but nonetheless blood relation) said: “The family of my aunt Julia is descended by her mother from the kings, and on her father's side is akin to the immortal Gods; for the Marcii Reges (her mother's family name) go back to Ancus Marcius, and the Julii, the family of which ours is a branch, to Venus. Our stock therefore has at once the sanctity of kings, whose power is supreme among mortal men, and the claim to reverence which attaches to the Gods, who hold sway over kings themselves."

I had a blackout here last night for about 3-4 hours, despite very little rain to alleviate a local drought, a branch fell down right in front of here. I went to Barnes and Noble for a/c, electric light, and all that good stuff. Last time I was there they had Toscano's Collapsable Poetics Theater, and one or two other cool things, but it was more BNey this time. No one told me there was a Library of America edition of early Ashbery! A sight to behold. I believe it was intentional that the blue ribbon placemarker is placed right at Joe Brainard's toilet in Vermont Notebook. It's actually cool to see Vermont Notebook in such a volume, the legit cover making it funnier, but it's odd to see Three Poems in there, sort of like it's become a 19th Century novella that comes in a 1200 page anthology for a survey course. Nothing else really fits in that thing. If I were a lot older that edition would make me feel old. I could say about other books there, this is workshoppy, that is workshoppy, after having skimmed them, but you already get that I think that way and the allegation would not surprise anyone about the poets in question. Finally it seems to be really raining here!

I had a blackout here last night for about 3-4 hours, despite very little rain to alleviate a local drought, a branch fell down right in front of here. I went to Barnes and Noble for a/c, electric light, and all that good stuff. Last time I was there they had Toscano's Collapsable Poetics Theater, and one or two other cool things, but it was more BNey this time. No one told me there was a Library of America edition of early Ashbery! A sight to behold. I believe it was intentional that the blue ribbon placemarker is placed right at Joe Brainard's toilet in Vermont Notebook. It's actually cool to see Vermont Notebook in such a volume, the legit cover making it funnier, but it's odd to see Three Poems in there, sort of like it's become a 19th Century novella that comes in a 1200 page anthology for a survey course. Nothing else really fits in that thing. If I were a lot older that edition would make me feel old. I could say about other books there, this is workshoppy, that is workshoppy, after having skimmed them, but you already get that I think that way and the allegation would not surprise anyone about the poets in question. Finally it seems to be really raining here!

08 July 2010

Going back to Palma Vecchio's Sea Storm, it has just come to my attention that that canvas is believed by at least a quartet of scholars, including Bernard Berenson, to have been originally conceived by Giorgione. One other new wrinkle is the belief that the sea monster on the lower left hand side was added in 1833 by Sebastiano Santi. I have another book that seems to think it was acquired by the Accademia in 1829, but it was apparently then in the Albergo della Scuola Grande di San Marco, which took liberties with its restorations. This all still predates Turner's sea monster but it's unclear to me whether Santi's monster, and, by extension, Turner's, was following a fashion or whether Santi's monster was a unique image. This is a developing situation and you are advised to check back for updates.

07 July 2010

As it takes little provocation for me to fixate on Giorgione, I have devoted some time this evening to the question: did Velasquez see Sleeping Venus before he painted the Rokeby Venus?

I'm not aware of any firsthand account of Velasquez commenting on Giorgione's painting or of his viewing it. Girolamo Marcello, who had owned two other Giorgione canvases, commissioned Sleeping Venus presumably in order to obtain “a talisman to guarantee Morosina and Girolamo an heir.” Though the painting is no longer at the Casa Marcello, the reproductive initiative seems to have been a success as it was Giralamo's descendent, himself called Count Giralamo Marcello, that in recent years put up Joseph Brodsky in Venice for which he became the subject of one of the Nobel Laureate's poems. Titian's Venus with a Mirror (below) was in the possession of the Barbarigo family during the time of Velazquez' visits to Venice. As Velasquez was both a famous painter and wealthy enough to amass his own collection of Venetian masters, it's not inconceivable that he visited these houses although not as inevitable as if they had been in museums.

Among the revelers at the 1694 Venice Carnivale was Augustus, younger brother of Johann Georg IV, Elector of Saxony, on one of his extended visits to the island town. Shortly after the festivities Augustus received word that his brother had died of smallpox and that he would become Augustus II, Elector. Over the course of the next few years Augustus, who would later become King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, bought up Venetian paintings for the Dresden palace, where Sleeping Venus hangs now, having been stashed away during the World War II bombing raids. Julius Caesar Augustus was believed in his time to be a descendent of Venus and was a patron of the arts, which may have affected Augustus II's resolve to obtain the canvas.

Among the revelers at the 1694 Venice Carnivale was Augustus, younger brother of Johann Georg IV, Elector of Saxony, on one of his extended visits to the island town. Shortly after the festivities Augustus received word that his brother had died of smallpox and that he would become Augustus II, Elector. Over the course of the next few years Augustus, who would later become King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, bought up Venetian paintings for the Dresden palace, where Sleeping Venus hangs now, having been stashed away during the World War II bombing raids. Julius Caesar Augustus was believed in his time to be a descendent of Venus and was a patron of the arts, which may have affected Augustus II's resolve to obtain the canvas.

Though there is no documentation of Velasquez visiting the Casa Marcello, recently notes have been discovered stating that during one of his trips to Italy, he chronicled the idea to paint Il Pordenone's Venus (right) in reverse - a close rip-off of Sleeping Venus with a red blanket underneath by a Giorgione disciple. The fact that he's so inspired by Pordenone's version indicates that Velasquez didn't, in fact, ever see Sleeping Venus, but was inspired by it indirectly.

Though there is no documentation of Velasquez visiting the Casa Marcello, recently notes have been discovered stating that during one of his trips to Italy, he chronicled the idea to paint Il Pordenone's Venus (right) in reverse - a close rip-off of Sleeping Venus with a red blanket underneath by a Giorgione disciple. The fact that he's so inspired by Pordenone's version indicates that Velasquez didn't, in fact, ever see Sleeping Venus, but was inspired by it indirectly.

Some suggest that the Rokeby Venus was an inspiration to Manet's Olympia, but there's no evidence that Manet ever saw the painting in person, and no reference of Manet's to a reproduction of it that I'm aware of. The Rokeby Venus was in a private collection in Yorkshire, which Manet never got to, from 1813 to 1905. This is a case of Velazquez and Manet both riffing off paintings that were inspired by Giorgione (by Titian and Pordenone) and coming up with a similar end result.

I was oblivious to Velazquez having seen a knockoff of Sleeping Venus when I shared my thoughts the other day about interiors and exteriors. Velazquez, first of all, was not a landscape painter as there was no admired tradition of landscapes in Spain at the time he worked save for El Greco who was not considered an influence, and since nudes in Spain were then painted for noblemen's bedrooms, perhaps he was disinclined to turn over a new leaf for such a client. The interior also makes the mirror more credible, enabling the portrait of the face which is essential to the effect of the work.

I'm not aware of any firsthand account of Velasquez commenting on Giorgione's painting or of his viewing it. Girolamo Marcello, who had owned two other Giorgione canvases, commissioned Sleeping Venus presumably in order to obtain “a talisman to guarantee Morosina and Girolamo an heir.” Though the painting is no longer at the Casa Marcello, the reproductive initiative seems to have been a success as it was Giralamo's descendent, himself called Count Giralamo Marcello, that in recent years put up Joseph Brodsky in Venice for which he became the subject of one of the Nobel Laureate's poems. Titian's Venus with a Mirror (below) was in the possession of the Barbarigo family during the time of Velazquez' visits to Venice. As Velasquez was both a famous painter and wealthy enough to amass his own collection of Venetian masters, it's not inconceivable that he visited these houses although not as inevitable as if they had been in museums.

Among the revelers at the 1694 Venice Carnivale was Augustus, younger brother of Johann Georg IV, Elector of Saxony, on one of his extended visits to the island town. Shortly after the festivities Augustus received word that his brother had died of smallpox and that he would become Augustus II, Elector. Over the course of the next few years Augustus, who would later become King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, bought up Venetian paintings for the Dresden palace, where Sleeping Venus hangs now, having been stashed away during the World War II bombing raids. Julius Caesar Augustus was believed in his time to be a descendent of Venus and was a patron of the arts, which may have affected Augustus II's resolve to obtain the canvas.

Among the revelers at the 1694 Venice Carnivale was Augustus, younger brother of Johann Georg IV, Elector of Saxony, on one of his extended visits to the island town. Shortly after the festivities Augustus received word that his brother had died of smallpox and that he would become Augustus II, Elector. Over the course of the next few years Augustus, who would later become King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, bought up Venetian paintings for the Dresden palace, where Sleeping Venus hangs now, having been stashed away during the World War II bombing raids. Julius Caesar Augustus was believed in his time to be a descendent of Venus and was a patron of the arts, which may have affected Augustus II's resolve to obtain the canvas. Though there is no documentation of Velasquez visiting the Casa Marcello, recently notes have been discovered stating that during one of his trips to Italy, he chronicled the idea to paint Il Pordenone's Venus (right) in reverse - a close rip-off of Sleeping Venus with a red blanket underneath by a Giorgione disciple. The fact that he's so inspired by Pordenone's version indicates that Velasquez didn't, in fact, ever see Sleeping Venus, but was inspired by it indirectly.

Though there is no documentation of Velasquez visiting the Casa Marcello, recently notes have been discovered stating that during one of his trips to Italy, he chronicled the idea to paint Il Pordenone's Venus (right) in reverse - a close rip-off of Sleeping Venus with a red blanket underneath by a Giorgione disciple. The fact that he's so inspired by Pordenone's version indicates that Velasquez didn't, in fact, ever see Sleeping Venus, but was inspired by it indirectly.Some suggest that the Rokeby Venus was an inspiration to Manet's Olympia, but there's no evidence that Manet ever saw the painting in person, and no reference of Manet's to a reproduction of it that I'm aware of. The Rokeby Venus was in a private collection in Yorkshire, which Manet never got to, from 1813 to 1905. This is a case of Velazquez and Manet both riffing off paintings that were inspired by Giorgione (by Titian and Pordenone) and coming up with a similar end result.

I was oblivious to Velazquez having seen a knockoff of Sleeping Venus when I shared my thoughts the other day about interiors and exteriors. Velazquez, first of all, was not a landscape painter as there was no admired tradition of landscapes in Spain at the time he worked save for El Greco who was not considered an influence, and since nudes in Spain were then painted for noblemen's bedrooms, perhaps he was disinclined to turn over a new leaf for such a client. The interior also makes the mirror more credible, enabling the portrait of the face which is essential to the effect of the work.

04 July 2010

The art critic Theophile Thoré correctly identified Manet's subject matter as rife with “borrowings and pastiches” of Velasquez, Goya, and El Greco, amid what he called the painter's “magical qualities.” Driven underground in 1848 by Cavaignac's provisional government, Thoré had resurfaced in '59 during Napoleon III's general amnesty to publish reviews under the name William Bürger, bringing the works of Vermeer and Hals from two centuries earlier to the attention of those outside Delft and Haarlem. Mindful of Manet's insecurities, Baudelaire struck back with a letter, lying through his teeth that Manet had never seen a Goya or an El Greco. Thoré, unconvinced, published the letter in Belgium, reiterating his praise of the painter: for all his borrowings he was the most original painter in Paris.

While pastiching the colors and subject matter of Iberia would produce in one critic such a minor qualification, pastiching the subject matter of Giorgione and Titian was, to the general art world, unforgivable, resulting in storms of insults and condemnations, deepening Manet's self-doubt and causing him to flee to Spain. This is no accident: the seeds of modernity cited in Baudelaire's essays on painting had already been sewn in the first decade of the 16th Century.

The events of the Paris Salon of 1863, in which 2800 canvases including those of Manet and Whistler were excluded, to be shown separately by Napoleon III's agreement in the Salon des Refusés, are often cited as the beginnings of Modernism. This rupture between the painters and the judges was set in motion a decade earlier by Courbet's The Bathers (above), which was removed from the 1853 Salon by the police and led to a change in the composition of the jury. The academic paintings of the Salon were full of nudes, but Courbet's pair was called “vulgar” by, amongst others, Delacroix for their body shape, pose and for being contemporary peasants rather than allegories of chastity and wisdom. In 1855, after Burial at Ornans and The Painter's Studio were rejected, Courbet set up an exhibition for himself across the street from the Salon, called "Realism." It was in 1855 that Baudelaire attacked Courbet's realist style: “the heroic sacrifice that Monsieur Ingres makes for the honor of tradition and Raphaelesque beauty, Courbet accomplishes in the interests of external, positive, immediate nature. They have different motives when waging war on the imagination, and the two opposing obsessions lead them to the same immolation.”

Several years later, Baudelaire wrote his seminal essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” in which he clarified his view of the dangers of separating the immediate and the Raphaelesque: “Beauty is made up of an eternal invariable element, whose quantity it is excessively difficult to determine, and of a relative, circumstantial element, which will be, if you like, whether severally or all at once, the age, its fashions, its morals, its emotions. Without the second element, which might be described as the amusing, enticing, appetizing icing on the divine cake, the first element would be beyond our powers of appreciation, neither adapted nor suitable to human nature. I defy anyone to point to a single scrap of beauty which does not contain these two elements.”

This essay wasn't published until November 1863, but had been written in early 1860, after which Baudelaire shopped it around a while. Manet valued Baudelaire's friendship, spent many hours with him, and the poet's opinions were an anchor against everything he chafed against, which inclined him to let his paintings be the embodiment of Baudelaire's theories.

Not only did, in fact, Courbet portray eternal beauty, but it's possible that his 1855 The Bathers was influenced by The Pastoral Concert, the 1508 painting hanging in the Louvre that is currently attributed to Titian, as the Reubenesque figure on the left of The Bathers is involved with water and draped around the leg. The painting was then attributed to Giorgione, and although dissenting opinion at that time suggested Palma Vecchio, the Titian theory didn't come onto the scholarly radar until the 20th Century. The figures look like Titian's, but the content, figures not relating to mythology, and the enigmatic subtext show the profound influence of older master Giorgione.

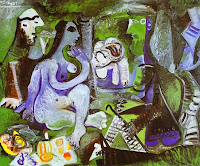

It's been stated frequently that when Manet, who rarely painted nudes, set out to produce one for the 1863 Salon, he used the situation of The Pastoral Concert with the figure poses of an engraving after Raphael's The Judgment of Paris. What isn't often noted is that the resulting canvas, Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, is the first intentional application of Baudelaire's credo, exemplified in advance by Titian and Giorgione. The two men in The Pastoral Concert are wearing contemporary clothing – one suggesting wealth, the other not - while the females – possibly present in the minds of the men - represent the eternal. The lute and the flute have represented the Appolonian and Dionysian opposition, with the flute being played here by a nymph and the lute by a scruffy male.

Manet, who has studied the painting enough to copy it, has replaced the nymph with the flute with a woman staring directly at the viewer, the model Victorine Meurent, herself a painter. I take this to suggest that the Dionysian function is being fulfilled by human observation, again in keeping with Baudelaire's theories. Nude women in traditional allegorical paintings of the Salon didn't look back at the viewer as Titian's Venus of Urbino did. As for Manet, whose early nudes (he only painted nine in his lifetime, most long afterward) stare at the viewer, let's recall that no one who pastiches Velasquez can ever wrest from their mind Las Meninas, where the Infanta Margarita stares back at the viewer, shown in the mirror to be the king and the queen. This representation of the viewer is an allegory of sight, since you, the viewer, are in fact standing in place of the king and the queen. Manet converts this allegory into a Dionysian function set forth by Baudelaire.

Manet, who has studied the painting enough to copy it, has replaced the nymph with the flute with a woman staring directly at the viewer, the model Victorine Meurent, herself a painter. I take this to suggest that the Dionysian function is being fulfilled by human observation, again in keeping with Baudelaire's theories. Nude women in traditional allegorical paintings of the Salon didn't look back at the viewer as Titian's Venus of Urbino did. As for Manet, whose early nudes (he only painted nine in his lifetime, most long afterward) stare at the viewer, let's recall that no one who pastiches Velasquez can ever wrest from their mind Las Meninas, where the Infanta Margarita stares back at the viewer, shown in the mirror to be the king and the queen. This representation of the viewer is an allegory of sight, since you, the viewer, are in fact standing in place of the king and the queen. Manet converts this allegory into a Dionysian function set forth by Baudelaire.

Picasso painted more pastiches of Le déjeuner sur l'herbe than any other painting. Las Meninas was another one he pastiched over and over, perhaps the runner up. He would spend 20 hours straight locked in his studio agonizing over these two paintings.

Picasso painted more pastiches of Le déjeuner sur l'herbe than any other painting. Las Meninas was another one he pastiched over and over, perhaps the runner up. He would spend 20 hours straight locked in his studio agonizing over these two paintings.

The angry reaction that Le déjeuner met from critics, the public, and some painters in 1863 is legendary; even Thoré called it “absurd.. inappropriate.. ugly.. and shocking” and the painter Jean-Léon Gérôme stipulated that his students not utter Manet's name. The legends can't reconcile why a knowing provocateur would be so emotionally shell-shocked by the reception he met, but I'm inclined to believe he was thrust into this role by Baudelaire and found the burden harrowing. This possibility is supported by the fact that Olympia, a nude in contemporary setting that created an even greater stir in the 1865 Salon, was painted before the 1864 Salon but not entered, and presumably entered the following year at Baudelaire's insistence.

In 1864 he entered two paintings: Incident in a Bull Ring and The Dead Christ With Angels (now at the NY Met), reverting to tried and true subject matter, which were immediately savaged by Theophile Gautier, leading to Manet destroying Incident. While Incident was a return to Goya, Dead Christ seems to me to be a return to Giorgione, who was near completion of a work of the same theme when he died, which was completed by Titian.

Olympia was accepted into the Salon of 1865 but the unprecedented critical vitriol and ridicule that met it is well documented. Again the figure stares the public in the face, and as people have guessed that the frog in Le déjeuner was a reference to prostitution, the name in the title was typically used in a brothel. Concurrent with Manet's discovery that Napoleon III was keeping a courtesan as a regular mistress, we have ourselves an interesting riff on Las Meninas, the courtesan taking the central position occupied by the princess to illustrate France under Napoleon III.

Olympia was accepted into the Salon of 1865 but the unprecedented critical vitriol and ridicule that met it is well documented. Again the figure stares the public in the face, and as people have guessed that the frog in Le déjeuner was a reference to prostitution, the name in the title was typically used in a brothel. Concurrent with Manet's discovery that Napoleon III was keeping a courtesan as a regular mistress, we have ourselves an interesting riff on Las Meninas, the courtesan taking the central position occupied by the princess to illustrate France under Napoleon III.

The influence of Titian's 1538 canvas Venus of Urbino (left) is universally acknowledged, but Titian's canvas is itself rooted in Giorgione's 1510 Venus Sleeping (below), which Titian is believed to have completed by filling in the landscape after Giorgione's death. The referencing of Venus Sleeping is illuminating: the physical ease, closed eyes, imperviousness to the exterior setting, and the gesture of the hand (which Twain complained upon seeing Urbino was masturbatory) contrasts with the penetrating stare, animated mood, social context, interior setting, and use of the hand to conceal the sex organ from the intruder in Olympia. Buddhists talk of the peace of closed eyes and wrath of open eyes, or Christ sleeping through the storm contrasted with his turning the tables at the Temple. Giorgione's Venus attempts to represent the mysteries of nature, while Olympia through Urbino uses the interior to explicate the man-made world, the psychology of class, transgression, and ambiguous interpersonal relations, emerging from an eternal eroticism.

The influence of Titian's 1538 canvas Venus of Urbino (left) is universally acknowledged, but Titian's canvas is itself rooted in Giorgione's 1510 Venus Sleeping (below), which Titian is believed to have completed by filling in the landscape after Giorgione's death. The referencing of Venus Sleeping is illuminating: the physical ease, closed eyes, imperviousness to the exterior setting, and the gesture of the hand (which Twain complained upon seeing Urbino was masturbatory) contrasts with the penetrating stare, animated mood, social context, interior setting, and use of the hand to conceal the sex organ from the intruder in Olympia. Buddhists talk of the peace of closed eyes and wrath of open eyes, or Christ sleeping through the storm contrasted with his turning the tables at the Temple. Giorgione's Venus attempts to represent the mysteries of nature, while Olympia through Urbino uses the interior to explicate the man-made world, the psychology of class, transgression, and ambiguous interpersonal relations, emerging from an eternal eroticism.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, painted by Manet two decades later, is believed to be another version of Las Meninas, again with the female staring at the viewer, and as with Le déjeuner and Olympia, the conventional belief that the woman in the painting is a prostitute. If Olympia was Napoleon's mistress looking back at the Emperor in the style of Velasquez, here the barmaid stares back at a bourgeois of the Third Republic setting up a paid tryst in bar that caters to ordinary male taste, perhaps intended in 1882 as an ironic celebration of the recent defeat of the monarchical restoration.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, painted by Manet two decades later, is believed to be another version of Las Meninas, again with the female staring at the viewer, and as with Le déjeuner and Olympia, the conventional belief that the woman in the painting is a prostitute. If Olympia was Napoleon's mistress looking back at the Emperor in the style of Velasquez, here the barmaid stares back at a bourgeois of the Third Republic setting up a paid tryst in bar that caters to ordinary male taste, perhaps intended in 1882 as an ironic celebration of the recent defeat of the monarchical restoration.

Though Michelangelo and Raphael were painting more famous works on the walls and ceilings of the Vatican at the time, I consider Giorgione's Sleeping Venus, 500 years old this year, to be the greatest exterior ever painted, and if it falls short of Las Meninas in the final round, it is perhaps only because the human mind is better suited to explore the dimensions of what it has built. Its pictorial qualities, most notably the color, are groundbreaking and infrequently exceeded, and its content contains not only the seeds of Manet's leap into modernity but the seeds of Surrealism.

While pastiching the colors and subject matter of Iberia would produce in one critic such a minor qualification, pastiching the subject matter of Giorgione and Titian was, to the general art world, unforgivable, resulting in storms of insults and condemnations, deepening Manet's self-doubt and causing him to flee to Spain. This is no accident: the seeds of modernity cited in Baudelaire's essays on painting had already been sewn in the first decade of the 16th Century.

The events of the Paris Salon of 1863, in which 2800 canvases including those of Manet and Whistler were excluded, to be shown separately by Napoleon III's agreement in the Salon des Refusés, are often cited as the beginnings of Modernism. This rupture between the painters and the judges was set in motion a decade earlier by Courbet's The Bathers (above), which was removed from the 1853 Salon by the police and led to a change in the composition of the jury. The academic paintings of the Salon were full of nudes, but Courbet's pair was called “vulgar” by, amongst others, Delacroix for their body shape, pose and for being contemporary peasants rather than allegories of chastity and wisdom. In 1855, after Burial at Ornans and The Painter's Studio were rejected, Courbet set up an exhibition for himself across the street from the Salon, called "Realism." It was in 1855 that Baudelaire attacked Courbet's realist style: “the heroic sacrifice that Monsieur Ingres makes for the honor of tradition and Raphaelesque beauty, Courbet accomplishes in the interests of external, positive, immediate nature. They have different motives when waging war on the imagination, and the two opposing obsessions lead them to the same immolation.”

Several years later, Baudelaire wrote his seminal essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” in which he clarified his view of the dangers of separating the immediate and the Raphaelesque: “Beauty is made up of an eternal invariable element, whose quantity it is excessively difficult to determine, and of a relative, circumstantial element, which will be, if you like, whether severally or all at once, the age, its fashions, its morals, its emotions. Without the second element, which might be described as the amusing, enticing, appetizing icing on the divine cake, the first element would be beyond our powers of appreciation, neither adapted nor suitable to human nature. I defy anyone to point to a single scrap of beauty which does not contain these two elements.”

This essay wasn't published until November 1863, but had been written in early 1860, after which Baudelaire shopped it around a while. Manet valued Baudelaire's friendship, spent many hours with him, and the poet's opinions were an anchor against everything he chafed against, which inclined him to let his paintings be the embodiment of Baudelaire's theories.

Not only did, in fact, Courbet portray eternal beauty, but it's possible that his 1855 The Bathers was influenced by The Pastoral Concert, the 1508 painting hanging in the Louvre that is currently attributed to Titian, as the Reubenesque figure on the left of The Bathers is involved with water and draped around the leg. The painting was then attributed to Giorgione, and although dissenting opinion at that time suggested Palma Vecchio, the Titian theory didn't come onto the scholarly radar until the 20th Century. The figures look like Titian's, but the content, figures not relating to mythology, and the enigmatic subtext show the profound influence of older master Giorgione.

It's been stated frequently that when Manet, who rarely painted nudes, set out to produce one for the 1863 Salon, he used the situation of The Pastoral Concert with the figure poses of an engraving after Raphael's The Judgment of Paris. What isn't often noted is that the resulting canvas, Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, is the first intentional application of Baudelaire's credo, exemplified in advance by Titian and Giorgione. The two men in The Pastoral Concert are wearing contemporary clothing – one suggesting wealth, the other not - while the females – possibly present in the minds of the men - represent the eternal. The lute and the flute have represented the Appolonian and Dionysian opposition, with the flute being played here by a nymph and the lute by a scruffy male.

Manet, who has studied the painting enough to copy it, has replaced the nymph with the flute with a woman staring directly at the viewer, the model Victorine Meurent, herself a painter. I take this to suggest that the Dionysian function is being fulfilled by human observation, again in keeping with Baudelaire's theories. Nude women in traditional allegorical paintings of the Salon didn't look back at the viewer as Titian's Venus of Urbino did. As for Manet, whose early nudes (he only painted nine in his lifetime, most long afterward) stare at the viewer, let's recall that no one who pastiches Velasquez can ever wrest from their mind Las Meninas, where the Infanta Margarita stares back at the viewer, shown in the mirror to be the king and the queen. This representation of the viewer is an allegory of sight, since you, the viewer, are in fact standing in place of the king and the queen. Manet converts this allegory into a Dionysian function set forth by Baudelaire.

Manet, who has studied the painting enough to copy it, has replaced the nymph with the flute with a woman staring directly at the viewer, the model Victorine Meurent, herself a painter. I take this to suggest that the Dionysian function is being fulfilled by human observation, again in keeping with Baudelaire's theories. Nude women in traditional allegorical paintings of the Salon didn't look back at the viewer as Titian's Venus of Urbino did. As for Manet, whose early nudes (he only painted nine in his lifetime, most long afterward) stare at the viewer, let's recall that no one who pastiches Velasquez can ever wrest from their mind Las Meninas, where the Infanta Margarita stares back at the viewer, shown in the mirror to be the king and the queen. This representation of the viewer is an allegory of sight, since you, the viewer, are in fact standing in place of the king and the queen. Manet converts this allegory into a Dionysian function set forth by Baudelaire. Picasso painted more pastiches of Le déjeuner sur l'herbe than any other painting. Las Meninas was another one he pastiched over and over, perhaps the runner up. He would spend 20 hours straight locked in his studio agonizing over these two paintings.

Picasso painted more pastiches of Le déjeuner sur l'herbe than any other painting. Las Meninas was another one he pastiched over and over, perhaps the runner up. He would spend 20 hours straight locked in his studio agonizing over these two paintings.The angry reaction that Le déjeuner met from critics, the public, and some painters in 1863 is legendary; even Thoré called it “absurd.. inappropriate.. ugly.. and shocking” and the painter Jean-Léon Gérôme stipulated that his students not utter Manet's name. The legends can't reconcile why a knowing provocateur would be so emotionally shell-shocked by the reception he met, but I'm inclined to believe he was thrust into this role by Baudelaire and found the burden harrowing. This possibility is supported by the fact that Olympia, a nude in contemporary setting that created an even greater stir in the 1865 Salon, was painted before the 1864 Salon but not entered, and presumably entered the following year at Baudelaire's insistence.

In 1864 he entered two paintings: Incident in a Bull Ring and The Dead Christ With Angels (now at the NY Met), reverting to tried and true subject matter, which were immediately savaged by Theophile Gautier, leading to Manet destroying Incident. While Incident was a return to Goya, Dead Christ seems to me to be a return to Giorgione, who was near completion of a work of the same theme when he died, which was completed by Titian.

Olympia was accepted into the Salon of 1865 but the unprecedented critical vitriol and ridicule that met it is well documented. Again the figure stares the public in the face, and as people have guessed that the frog in Le déjeuner was a reference to prostitution, the name in the title was typically used in a brothel. Concurrent with Manet's discovery that Napoleon III was keeping a courtesan as a regular mistress, we have ourselves an interesting riff on Las Meninas, the courtesan taking the central position occupied by the princess to illustrate France under Napoleon III.

Olympia was accepted into the Salon of 1865 but the unprecedented critical vitriol and ridicule that met it is well documented. Again the figure stares the public in the face, and as people have guessed that the frog in Le déjeuner was a reference to prostitution, the name in the title was typically used in a brothel. Concurrent with Manet's discovery that Napoleon III was keeping a courtesan as a regular mistress, we have ourselves an interesting riff on Las Meninas, the courtesan taking the central position occupied by the princess to illustrate France under Napoleon III. The influence of Titian's 1538 canvas Venus of Urbino (left) is universally acknowledged, but Titian's canvas is itself rooted in Giorgione's 1510 Venus Sleeping (below), which Titian is believed to have completed by filling in the landscape after Giorgione's death. The referencing of Venus Sleeping is illuminating: the physical ease, closed eyes, imperviousness to the exterior setting, and the gesture of the hand (which Twain complained upon seeing Urbino was masturbatory) contrasts with the penetrating stare, animated mood, social context, interior setting, and use of the hand to conceal the sex organ from the intruder in Olympia. Buddhists talk of the peace of closed eyes and wrath of open eyes, or Christ sleeping through the storm contrasted with his turning the tables at the Temple. Giorgione's Venus attempts to represent the mysteries of nature, while Olympia through Urbino uses the interior to explicate the man-made world, the psychology of class, transgression, and ambiguous interpersonal relations, emerging from an eternal eroticism.

The influence of Titian's 1538 canvas Venus of Urbino (left) is universally acknowledged, but Titian's canvas is itself rooted in Giorgione's 1510 Venus Sleeping (below), which Titian is believed to have completed by filling in the landscape after Giorgione's death. The referencing of Venus Sleeping is illuminating: the physical ease, closed eyes, imperviousness to the exterior setting, and the gesture of the hand (which Twain complained upon seeing Urbino was masturbatory) contrasts with the penetrating stare, animated mood, social context, interior setting, and use of the hand to conceal the sex organ from the intruder in Olympia. Buddhists talk of the peace of closed eyes and wrath of open eyes, or Christ sleeping through the storm contrasted with his turning the tables at the Temple. Giorgione's Venus attempts to represent the mysteries of nature, while Olympia through Urbino uses the interior to explicate the man-made world, the psychology of class, transgression, and ambiguous interpersonal relations, emerging from an eternal eroticism.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, painted by Manet two decades later, is believed to be another version of Las Meninas, again with the female staring at the viewer, and as with Le déjeuner and Olympia, the conventional belief that the woman in the painting is a prostitute. If Olympia was Napoleon's mistress looking back at the Emperor in the style of Velasquez, here the barmaid stares back at a bourgeois of the Third Republic setting up a paid tryst in bar that caters to ordinary male taste, perhaps intended in 1882 as an ironic celebration of the recent defeat of the monarchical restoration.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, painted by Manet two decades later, is believed to be another version of Las Meninas, again with the female staring at the viewer, and as with Le déjeuner and Olympia, the conventional belief that the woman in the painting is a prostitute. If Olympia was Napoleon's mistress looking back at the Emperor in the style of Velasquez, here the barmaid stares back at a bourgeois of the Third Republic setting up a paid tryst in bar that caters to ordinary male taste, perhaps intended in 1882 as an ironic celebration of the recent defeat of the monarchical restoration.Though Michelangelo and Raphael were painting more famous works on the walls and ceilings of the Vatican at the time, I consider Giorgione's Sleeping Venus, 500 years old this year, to be the greatest exterior ever painted, and if it falls short of Las Meninas in the final round, it is perhaps only because the human mind is better suited to explore the dimensions of what it has built. Its pictorial qualities, most notably the color, are groundbreaking and infrequently exceeded, and its content contains not only the seeds of Manet's leap into modernity but the seeds of Surrealism.

03 July 2010

My World Cup loyalties tend to center on whether I have most recently read a book by an author from a particular country. Now there's only one non-European team, Uruguay, so it's Benedetti and Onetti vs. the History of the Novel, except that they would probably root for the history of the novel.

My World Cup loyalties tend to center on whether I have most recently read a book by an author from a particular country. Now there's only one non-European team, Uruguay, so it's Benedetti and Onetti vs. the History of the Novel, except that they would probably root for the history of the novel.During the tournament there are inevitably articles speculating why the US favors American football rather than “soccer.” I'm inclined to think that allegiances to sport are contingent on the physical size of the upper class, and countries where the upper class is physically smaller are going to favor a sport where smaller people can excel. American football is descended from rugby, a sport where large men push each other around, and, in England, the upper classes insulate themselves from a possible challenge from lower class men through the distinction of Rugby Union and Rugby League, just as British crew maintains its hierarchy by giving last year's winners a head start. Rugby is popular amongst the German upper class while soccer is apparently the working class sport. Americans in the mid-19th Century were some three inches taller than Germans on average, even though the country's full of German blood by way of England or not. American football introduced more law enforcement and incessant discussion, and my attempts to stop watching it have been unsuccessful. Basketball (which I used to watch but have managed – cross my fingers – to kick) is likewise a sport that favors the tall. Baseball favors the tall in certain instances (pitching, first base, etc.) but the fact that it is easier for shorter players to overcome this accounts for it being the US's most popular athletic export, winning over Latin America and East Asia.*

After Jim Crow the question of whether to integrate the sports came into play, and after much resistance, white people let black people play, leading to the worldwide phenomenon of the black basketball star. Rush Limbaugh tries to discourage the black quarterback (which led to my pulling for McNabb and the Eagles and the ensuing addiction) because the idea that the team is best managed by a white administrator-athlete enables people of that mindset to maintain their competitive disposition. People in Blue States have moved on to playing soccer, presumably to escape the perception of immanent physical injury associated with football, leading to Republican concerns in 1996 that the Democratic lead was attributed to “soccer Moms,” while people in Red States stick to the gridiron. Also, immigrants from countries of shorter people tended to concentrate in the Northeast and in California, and the shorter people were more likely to play soccer and vote Democratic.

After Jim Crow the question of whether to integrate the sports came into play, and after much resistance, white people let black people play, leading to the worldwide phenomenon of the black basketball star. Rush Limbaugh tries to discourage the black quarterback (which led to my pulling for McNabb and the Eagles and the ensuing addiction) because the idea that the team is best managed by a white administrator-athlete enables people of that mindset to maintain their competitive disposition. People in Blue States have moved on to playing soccer, presumably to escape the perception of immanent physical injury associated with football, leading to Republican concerns in 1996 that the Democratic lead was attributed to “soccer Moms,” while people in Red States stick to the gridiron. Also, immigrants from countries of shorter people tended to concentrate in the Northeast and in California, and the shorter people were more likely to play soccer and vote Democratic.With professional sports came the Team Owner. In horse racing, the owner of the horse is understood to be the protagonist, which allows the sport to maintain the favor of a certain culture. The oil man Jerry Jones was recently voted one of the most hated figures in football despite running the team rather effectively and wanting feverishly to win, taking over the mantle of baseball's retired defense contractor George Steinbrenner. The fans enter into a difficult emotional relationship with this protagonist: they resent their enormous net worth more than the simple snob with a good salary as well as their power and lack of accountability, but still share the owner's aspirations to win and invest their self-image in the success of the team, which symbolizes the success of the region's economic base.

*I remember shooting hoops in a small Mexican town with an African-American surfer from California, concerned that a game would ensue and that I had only brought sandals with me on this day trip. The school got out and all the local kids ran up to him, completely ignoring me, begging him to teach them basketball.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)