|

| New York as Seen from Across the Body, 1913 |

As the Picabia show, which readers in these parts had herein been implored to see, is being taken down I’ll type some more with its glow still fresh. Amongst other things, it afforded the spectacle of Picabia quotations offered to the masses going up the Metro escalator at 53rd and 5th, a set of three or four including “I am a beautiful monster," “civilization created crime" and “live for your pleasure" rotated as Madison Avenue-style brainwashing sparing commuters a larger set that could include “Happiness is to command no one and not be commanded.” “The world is steeped in sticky good taste and ignorance.” “There is no truth true to life” “Misery is illustrious like a triumphant god with circular gestures” “Newspapers are daily leeches which you place in a crown around your head.” “‘Why do you write?’ Francis Picabia: I don’t know and I hope I never know.” “If you read Andre Gide aloud for ten minutes, your breath will stink.” “Art is a pharmaceutical product for imbeciles.” “War makes me want to laugh.” “I surpass amateurs, I am the super-amateur; professionals are shit-pumps.” “‘All the plants belong to me, that’s why I don’t like the country!’” “Don’t be fooled: artists are dry cleaners.” “Life is today and today doesn’t exist.” “Artists are the result of nature’s miserliness.” “There is only one way to save yourself: sacrifice your reputation.” “Genius lies in ignoring others.” “Art is the worship of error.” “To fear the senses is to become a philosopher.” “Where art appears, life disappears.” “It’s better to suffer than be surrounded by scarecrows.” To Duchamp, Picabia was “a negator. With him it was always, ‘Yes, but..’ and ‘no, but..’ Whatever you said, he contradicted. It was his game. Perhaps he wasn’t aware of it.”

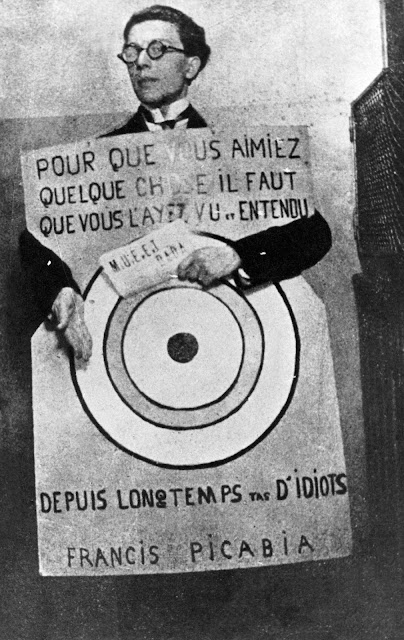

As with MoMA‘s wonderful presentation of Lygia Clark, the perplexed reviews tell you the artist has steered their vessel off the flat earth. I hadn’t read Financial Times’ Ariella Budick on Broodthaers, but as Clark, Broodthaers, and Picabia each added to art something it hadn’t seen before which has to this day been only partially excavated and tagged by others, her reviews have scored the trifecta of cluelessness towards anything that cannot be reduced to well-trodden art theory mantras. “These products of Picabia’s nadir have re-emerged, not to be redeemed, but to suggest that their maker was something darker than a mere prankster or provocateur. At MoMA, he comes across as a spectacularly talented but insubstantial nihilist, an anti-artist propelled by the vacuum in his soul.” As Picabia, the poet Max Jacob referred to as Tzara-thustra, and Bataille were the leading devotees of Nietzsche among Parisian modernists, she is parroting the lazy and inaccurate shorthand of “Nietzsche the nihilist” while anyone who actually reads Nietzsche ('Pour que vous aimiez quelque chose il faut que vous l’ayez vu et entendu depuis longtemps tas d’idiots') knows his entire oeuvre was involved in overcoming nihilism, saying art was a primary tool to do so, which drove Picabia to find belief in his own creations and discoveries rather than dogmatics, discoveries essential to both modernism and post-modernism with an impact only a handful in art can claim.

Burdick on his mid-40s works: “The mixture of turpitude and Aryan-friendly realism is troubling. It’s not clear whether he was cozying up to Vichy fascists or lampooning them, flattering through imitation or protesting with satire.” Quoting Petras again contextualizes the source “The editors and columnists (of FT) have supported wars destroying the Libyan, Iraq, Syrian and Ukrainian economies..” in the case of the Ukraine, directly supporting neo-Nazis; in the case of Syria, supporting those who funded ISIS at a critical juncture. Picabia: “I have no intention of talking politics, that’s something I absolutely loathe..” Nietzsche's "Strict war discipline.. superiority of the leaders, unity and obedience among the led.. have nothing to do with culture” becomes Picabia's “A clan of nonentities .. cut off the heads of those who represent force and intelligence, who represent an aspiration of something better..” the "obedience among the led" illustrated in 1942‘s Adoration of the Calf (left). “Dear revolutionaries your ideas are as limited as a petit bourgeois from Besançon..”

Nietzsche respected Buddhism but eventually found it lacking the individual affirmation that could overcome nihilism. Breton to Picabia in 1952: “Tell me, was not Dada perhaps, at its best, a flake of Zen wafted as far as ourselves?” Picabia’s “Andre Breton and I have never been on bad terms, the rumors going around are stupid made-up stories dictated by idiots” was by all accounts the case, but the way they agreed to disagree on aesthetic matters, in my view, reflected the latent rift between Picabia the Nietzschean and Breton the Hegelian, the source of which predates Nietzsche, commencing when his “educator” Schopenhauer loathed the popular Hegel ("the clumsy charlatan") so much he scheduled his Berlin lectures at the same time. Hegel believed in the inevitability of the state though his has been, as Walter Kaufmann noted, exaggerated; Picabia joins Nietzsche in aversion to the herd. Rousseau, admired by Breton, was dialectically superseded for Nietzsche by Goethe’s Faust. The Freudian-influenced Breton wrote appreciatively in the Anthologie de l'humour noir “Nietzsche’s whole enterprise in fact tends to justify the superego by increasing and expanding the ego.. to restore to man all the power he had invested in the name of God. It might be that the ego dissolves at that temperature..”

In that 1952 letter Breton wrote Francis "I would like you to read (Daisetz T. Suzuki's Zen Doctrine of No-Mind), because if anyone has set himself the task proposed in this book, of transcending discrimination in all forms, it is certainly you." In Zen "no-mind" the innate non-discrimination of perceived entities stands apart from conditioned notions of dualism, closely resembling Breton’s “supreme point” noted in the Second Manifesto, which I’ve seen as an epigraph for a book about the Dalai Lama: “Everything leads us to a point in the spirit in which life and death, real and imaginary, past and future, communicable and incommunicable are no longer perceived as contradictions. It would be in vain to look for any other motivation in surrealist activity than the hope of determining this point.” My immediate impressions upon reading the Suzuki doctrine was that it bore an uncanny resemblance not just to this point but also to Breton’s “communicating vessels,” first formulated in his 1928 essay Surrealism and Painting which mentions Picabia amongst many others (over twenty years before the Suzuki translation became available in French), but since he wrote Communicating Vessels thereafter during what Michel Carrouges called in 1950 “the period when Marxism exercised its strongest hold on Breton” he could not reconcile the Eastern asceticism with Hegelian dialectical materialism, relating it rather to Picabia’s version of Dada unencumbered by materialism. Deleuze: “The dialectic is the natural ideology of ressentiment and bad conscience. It is thought in the perspective of nihilism and from the standpoint of reactive forces.. powerless to create new ways of thinking and feeling"

Communicating Vessels was published in 1932, wherein Carrouges notes that in an elaboration of the supreme point “life for the sake of life and of Revolution” replaces past/ future and life/ death, saying elsewhere “..the supreme point can remain for the surrealists the place, at once real and ideal, where all antimonies are resolved, the meeting place of all the divine energies that Nietzsche dreamed of recuperating.” In 1937, after his formal break with Moscow, Breton wrote about the supreme point “these antimonies, cruelly felt, must be gotten rid of.. this suffering..” which sounds Buddhist. In 1955 Ferdinand Alquié, picking over Carrouges’ interpretations, went to to great pains to downplay Breton’s concern for dialectical materialism, quoting Wolfgang Paalen in 1953 “(Hegel’s) philosophy permits the justification of all the totalitarian regimes,” but concedes “Breton could not but admire in Hegel the will to negate all transcendence or, which amounts to the same thing, to project all transcendence onto a horizontal plane” which itself sounds like Zen.

Breton’s selection for Nietzsche in the Anthologie de l'humour noir was a flight of non-discrimination, Friedrich’s letter to Jacob Burckhardt in 1889:

‘I have reserved myself a small student’s room.. I pay twenty-five francs, including service, buy my tea, and do all my shopping myself, suffer from torn shoes, and thank heaven every moment for the old world for which men have not been simple and quiet enough..

‘What is disagreeable and offends my modesty is that at bottom I am every name in history..

‘Tomorrow my son Umberto will come with the lovely Margharita, whom, however, I shall also receive here only in shirt-sleeves. The rest for Frau Cosima - Ariadne - from time to time there is magic.’

The communicating vessels, as described by Breton and illustrated by Rivera..

resembles the visual schema in Doctrine of No-Mind, while Picabia’s Transparencies intuit the doctrine, applying it to modes of sacred and profane representation in the West, providing both form and content to Polke's drama of the consciousness.

|

Some have speculated Picabia was hinting Breton was the central figure of Dresseur d'animaux (below) and Picabia the owl, but Breton’s letter of 1952 hinted that the Zen master ‘Shih-kung Hui-tsang of Foochow’ profiled by Suzuki could have unwittingly been the main figure in Dresseur d'animaux, as Picabia intentionally interrupted the outlines of him and the animals to portray him as the lord of illusion before Magritte adopted that theme.

Becoming, important to Nietzsche, appears in Breton’s 1946 “In Haiti at night..” “Bearing witness as no other and always quivering as if weighed in the balance of leaves, like egrets taking wing from the face of the pond where today’s myths are born, the art of Wifredo Lam streams out from the point where life’s springwaters reflect the mystery tree, by which I mean the preserving soul of the race, so as to shower with stars the becoming that must be for the betterment of humanity.” The half-Cuban Picabia’s postwar works in his final period seem to be more distantly indebted to the liberties Lam took with Afro-Cuban iconography.

Where Picabia primarily departed from Duchamp, beginning with the machine period, was his will to discover in what Marcel pejoratively called the retinal something unknown and to believe in nothing else. “‘Mr. S.S., of high Persian nobility’ praised Francis 'the truly beautiful thing is to paint an invention well. This gentleman - Cezanne, as you call him - has the mind of a greengrocer’” recounted Breton in 1922, the same year he wrote to Francis “the more I think about it, the more I feel I have always loved you.” At one visit I saw two elderly women riding down the escalator, one pointing to the large photo of Picabia “now that was good!” What glows is a spirit that could not be consumed in him or anyone that cares about him, a treasure map that the earliest modernists held from their first steps with more surprises to come. “I prefer not to spoil the surprise.”